This week I’m loving

This week’s love goes out to a little article highlighted by Adam Grant that might be just the thing most generalists need.

In the article Adam Mastroianni introduces “The Coffee Beans Procedure”. A way of mentally unpacking an imaginary preview of the future to validate its assumptions. We need this because:

Our imaginations are inherently limited; they can’t include all details at once.

As generalist project managers we like to think in details to a degree. However, not everyone does this. In fact, probably most of your project team isn’t seeing the details…just their imaginary vision of the future. You can help make them more aware of everything they are not seeing by asking questions that help them unpack it.

Unpacking is easy and free, but almost no one ever does it because it feels weird and unnatural. It’s uncomfortable to confront your own illusion of explanatory depth, to admit that you really have no idea what’s going on, and to keep asking stupid questions until that changes.

Thinking about taking a new direction on as a generalist? Wondering if it is the right fit? Think about moving, think about all the boxes you’d take with you. Then, slice them open, and dig into what is inside them? Which treasured trinkets are your essentials? Which boxes contain the junk you are hauling around but should actually let go of? Once you know your list of things that make you happiest and most productive, examine, what jobs actually are those things? I loved the example in the article of the job of a professor:

…in grad school I worked with lots of undergrads who thought they wanted to be professors. Then I’d send ‘em to my advisor Dan, and he would unpack them in 10 seconds flat. “I do this,” he would say, miming typing on a keyboard, “And I do this,” he would add, gesturing to the student and himself. “I write research papers and I talk to students. Would you like to do those things?”

When I was at University, I was initially enrolled in the “research stream” for my biochemistry degree program, one that would take me into a professorial career and a PhD track if I wanted (and which did for several of my friends). But I realized, you know, I’m not that “into research” and in my final year I dropped out of that stream into the “Specialization” stream. So my degree says I have a BSc with Specialization in Biochemistry. It turns out, this might have been my first generalist moment in my career, and it was certainly my best year at University. With all my spare time vacated by exiting a bunch of required chemistry courses and labs, I took Anthropology of Science and Technology, Botany of Drug Plants, and Comparative Literature. I became a Teaching Assistant for undergraduate chemistry and taught 5 lab sections while completing a full course load for the year. Many people ask me then, how I ended up in a project management career marked by years of research and development work in various industries. At first glance, as someone who wasn’t “into research” I can see why. But when I unpack this box here’s what it really is:

I liked the effort of discovery. It was what drew me to science in the first place. But I didn’t want to “write papers on it”. I wanted to execute discovery into the tangible. That’s why I became a project manager.

I like applied science. Now they teach this more comprehensively in school, and I might have figured this out in my younger days, if I had the schooling available now, then. Because I like applied science, I don’t want to do science for the sake of science. I want to do science that makes lives better, science that translates. I smelled that this was a rare outcome in academics, and wisely exited that career path.

More importantly, overall, I like doing things from a grounding in method. I’m fascinated by how frameworks contain chaos into productivity. I like the experience of learning through step-wise experimentation along a path of discovery. Science gave me a framework for life.

So you could sum up my career as a project manager as this:

I like using methodical approaches to build and execute new things through incremental experiments that translate discoveries into real world impacts.

What did you discover when you unpacked your boxes?

From the Practice

This week’s practice-focused segment highlights a great little read on shifting your mindset from “failing” to “learning”. David Pereira talks about the presence of “fail faster” culture in agile projects and organizations, and how instead, this might be framed as a “learn fast” culture.

If we’re honest with ourselves, failing is one of the things we hate the most.

Instead of failing fast, Pereira proposes we use a method of “de-risking” ideas. I love his simple framework for this, and think every team should use it:

How do we ensure customers want what we build? (Desirability)

How do we collect business value? (Visibility)

How can we deliver within the constraints we are facing? (Feasibility)

How do we ensure users successfully interact with what we build? (Usability)

After you know the answers to these questions, test them with experiments before going all in. With each experiment, make sure you take time to learn whether the assumptions you made around your idea are working. Then, instead of creating a fail fast culture, you have successfully built a learn fast culture instead!

An interesting read

Since project management is rapidly shifting to strategic execution, every project manager needs to be able to level-up their strategy skills. This week I came across an excellent framework that is easily applied by project managers to every project we face, and, importantly, this framework helps you at the point of project design/conception; an area where many of us struggle with a lack of tools.

It’s called the 5C framework and you can read the explanation of it from Maarten Dalmijn here.

I’m going to focus on how I think this applies for project leaders.

At the beginning of a project we know what we are undertaking something new to address something, overcome something, change something, or build something. The first ‘C’ in the framework is “Challenge”. The secret here is in framing it. Do you understand the problem you are trying to solve? The value you are trying to deliver? How deeply do you understand it? Where we can add our secret sauce in project management is in how this is articulated (and usually this would be in the Overview or Introduction to the Project Charter).

Next, you need to identify your “Constraints”. I write these right into my project charter, but knowing them at the conception of your project is important because it might even shape your approach to the project. Constraints can also help you define your scope.

Once we can see the landscape we are working within from our list of Constraints, we will be able to focus on our “Concessions”. Now this is something very important that we don’t talk often about in projects. Where will your trade-offs be? What will you give up to get where you need to go, given the constraints? These are incredibly important conversations you have with your Sponsor and your Stakeholders, and now they have a home in your process.

After we have ironed our Concessions out we ask ourselves the most important question: can we go forward? Here, everyone from your Sponsor to your Project Team members, is making a courageous decision to embark on a journey no one knows in full and no one has done before. This takes Courage, and it is important to remember that this is what you are asking of everyone. Examining alignment and agreement from the lens of “Courage” can be extremely helpful to assessing your stakeholder risks, Understanding your gaps in “Courage” may inform your communications strategy and your stakeholder management.

As you reach the end of this framework applied to projects, you should have a project charter and plan and this “Clarity” is the secret to successful strategic execution. With a clearly framed Challenge, everyone knows why you are doing what you are setting out to do. Because you have surfaced Constraints, and asked for Concessions, everyone knows the terms they are buying into the project on. Since you’ve made the decision to proceed, everyone has mustered up their Courage and this will help the team continue to move forward in the face of the obstacles it will no doubt encounter. And as the going gets tough, you’ve got everything documented to remind everyone of the Clarity that has been agreed to, should they lose sight of it. These are the ingredients for successful strategic exectuion, and now, you’ve got a consistent approach to every project you start that will help to ensure its success!

A great strategy requires you to be smart and stupid at the same time. You need to have the brains to see what’s possible and be stupid enough to leap when it scares the hell out of you.

A tip

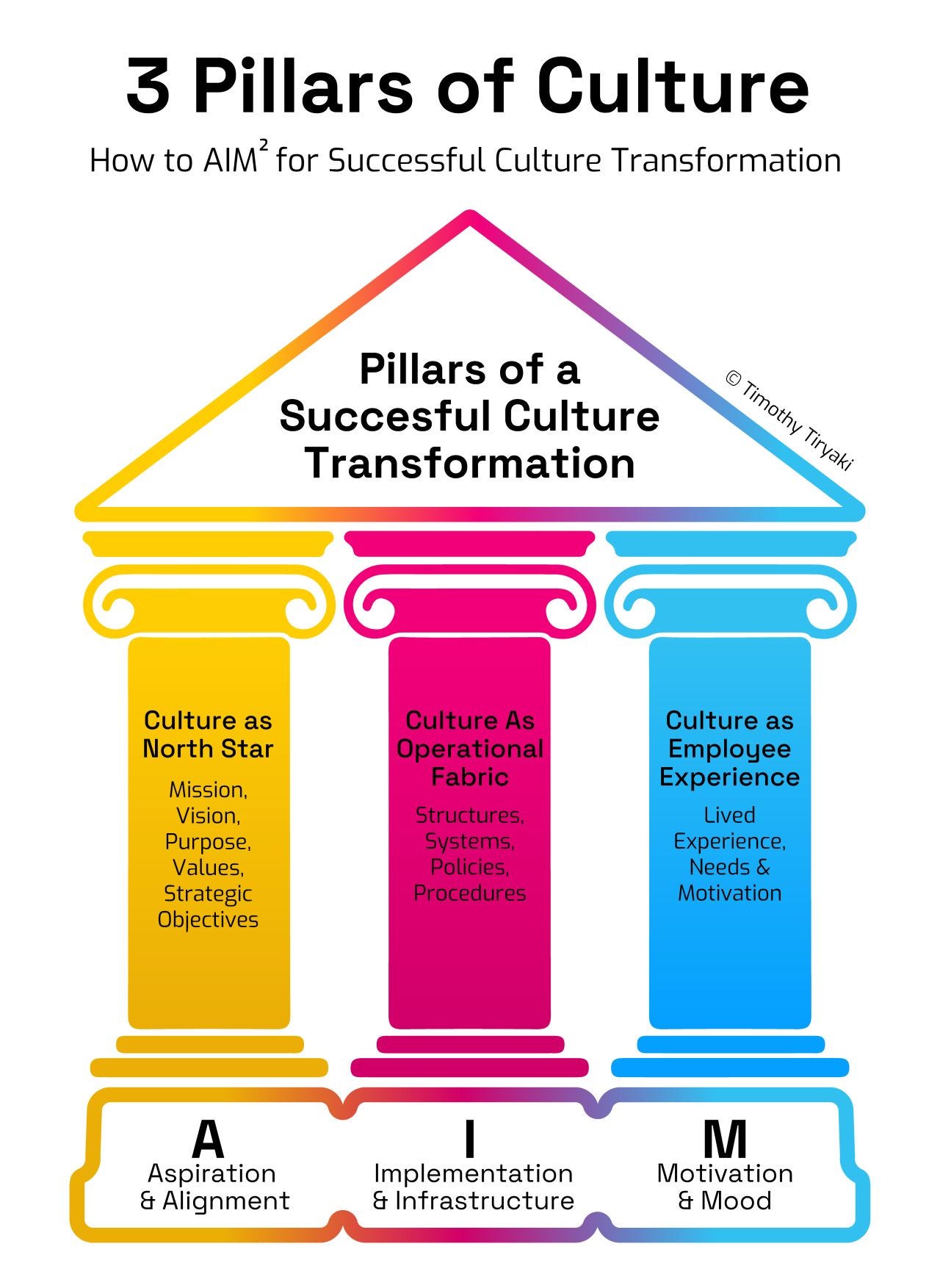

If you ever wondered why, as a project manager, you are touching so many aspects of your organizational fabric, this is why:

Image credit: Timothy Timur Tiryaki - LinkedIn

You keep the team focused through aspiration and alignment. You help to design, implement, and influence the infrastructure that gets things done and you are always managing and setting motivation and mood for your team.

Agree, or disagree?

A lesson

This week’s lesson is a carousel of great reminders about our work-life balance habits and some habits you may want to re-assess. Just ignore that the tips are written for CEOs, you are a CEO of your project and we know you have these bad habits too!

My favorite takeaway: Be the leader who models healthy boundaries!